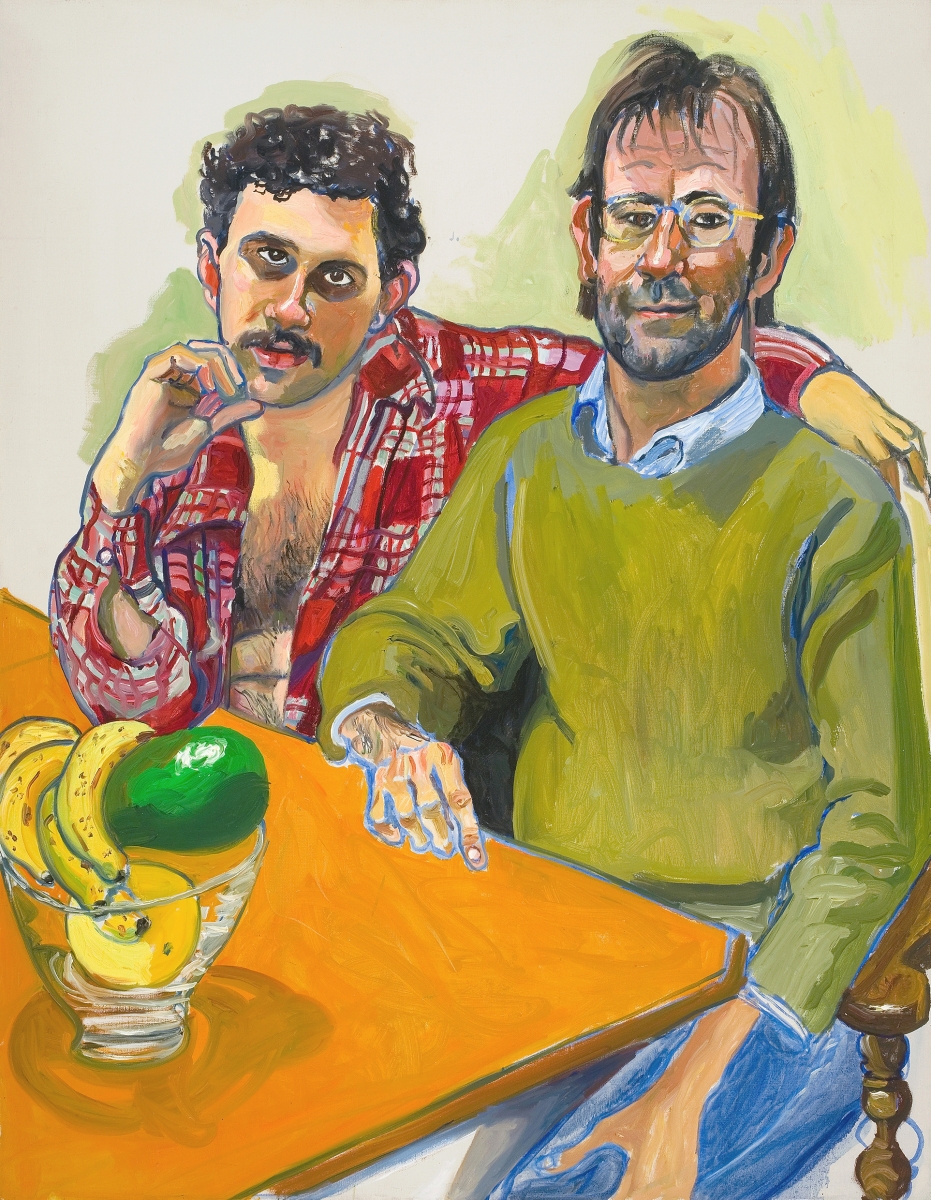

“Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd” by Alice Neel, 1970. Oil on canvas, 60 by 41- inches. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna Jr Fund. ©The Estate of Alice Neel.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NEW YORK CITY – “People come first,” said Alice Neel in a 1950 interview for the Daily Worker. “My work is a monument to them.” Best known today for her alluring yet disquieting portraits of 1970s counterculture types, the painter Alice Neel had a career that was much longer and more varied than many recognize. Born in 1900, she came of age as a professional artist in the late 1920s and 1930s, and from the beginning she integrated her art with her political and personal lives, both of which were complex and chaotic. Her overriding humanism is a constant throughout her broad body of work, which includes landscapes, cityscapes, still lifes and genre-defying works on paper as well as the painted portraits that have captured lasting public consciousness. “Alice Neel: People Come First” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through August 1.

The “signature image” for the exhibition, co-curator Randall Griffey says, is the portrait of fellow artists Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian Buczak, who were a couple; however, a case could also be made for the double portrait of gender-bending performers and Warhol Factory stars Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd. Both paintings are typical of the work Neel produced in the 1970s that has earned her lasting fame and adulation, equally as painter qua painter and as a hero of the marginalized. Painted in the artist’s home studio, the works convey what has come to be seen as her signature style. The figures are drawn directly onto the canvas, their firm outlines filled in with luscious and vibrantly colorful swaths of paint, set against backgrounds of largely unfinished raw canvas. “The color is extraordinary,” says co-curator Kelly Baum. “Every shadow is made up of several different colors; she gives the body volume by adding color… There’s a specific kind of pink – it’s not neon pink but it’s a very bright pink – and you see it at the tips of the fingers and toes of the sitters.” Her sitters confront the viewer head-on, posed intimately and informally and yet with a certain stiff reserve. They are painted as they are – no idealizing force is at play here – and yet there is a sense that they are not entirely comfortable, whether in their own skin or under the power of Neel’s uncompromising gaze.

Alice Neel, 1944. Alice Neel Archive, Stowe, Vt. Photograph by Sam Brody. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel.

“It’s easy to get drawn into the drama of the sitters,” says Baum, stressing the importance of confronting the paintings as paintings and not simply as glosses on the lives of their subjects or creator. Nevertheless, the “people come first” paradigm of the show encourages a consideration of the people on both sides of the canvas, and this full accounting of Neel’s career more or less demands it. Baum describes Neel as a “radical humanist,” the title of the catalog introduction coauthored by Baum and Griffey. Throughout her adult life, Neel participated actively in left-wing causes, including worker’s rights, anti-lynching campaigns, the feminist movement and advocacy related to the representation (or lack thereof) of women and people of color in art museums. These fervent concerns are visible in her art, which in the early part of her career she shared and distributed primarily through left-wing periodicals like the Daily Worker and Masses & Mainstream.

Baum and Griffey write that “Neel’s humanism was initially forged in the crucible of 1920s Cuba,” where she moved to be with her husband, Carlos Enriquez, who had been expelled from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her 1926 portrait of Enriquez conveys a certain darkness and distance, and indeed the marriage did not last. However, as Neel departed for New York’s Greenwich Village in 1927, she took with her the highly developed understanding of the challenges faced by marginalized people that she had shared with Enriquez.

“Ninth Avenue El” of 1935, for instance, shows the bent figures of workers trudging home at the end of a long workday. Here the people pictured are more symbols than individuals, but Neel was also doing portraiture at the time, primarily of creative and politically engaged people like herself (“Kenneth Fearing,” 1935, and “Elenka,” 1936). People of color become increasingly visible in her work after her 1938 move to Spanish Harlem, where she was enthralled with the culture of the street and the pervasiveness of communal family life. Images of her own extended family (“The Spanish Family,” 1943) blend and merge with those of her neighbors (“Dominican Boys on 108th Street,” 1955). Works like “T.B. Harlem” (1940), which shows her lover’s brother being treated for tuberculosis, address the intersecting hardships of racism, poverty and ill health in the late-Depression United States. That same sensitivity to her subjects, the pathos without pity that we see in her later work, was already in place some 30 to 40 years before.

2.jpg)

Installation view of “Alice Neel: People Come First” at The Met, 2021. Image Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen.

Neel was an ardent feminist, if not a completely by-the-book one. Her personal history was marked by a series of tragedies connected to her gender – the dissolution of a marriage that left her in poverty, the loss of one daughter to a custody agreement and another to diphtheria, her own struggles with mental health and treatment – which made bolstering the rights of women more than just an academic concern. Her early works on paper convey her feminist ideals as fully as anything she made, partly because those that exist today barely survived an egregious act of domestic violence by her then-partner, Kenneth Doolittle, who set them on fire in 1935. “What survived makes you mourn the loss even more,” says Baum, “because they’re extraordinary. What you see in those works on paper is Neel developing her feminism… Those works are funny, they’re heartbreaking, they’re poignant, they’re sexy, and they’re so deeply politicized… She’s starting over fresh in the city and she just starts making revolution after revolution – political, professional, sexual – and it’s all in this body of paper.”

Still, Neel had a prickly relationship with feminism. “She joined the feminist movement in the 1970s but bickered with feminists all the time,” says Baum. Neel seems to have been somewhat nonplussed about the prominence of lesbians within the movement’s leadership. Some lesbians who sat for portraits with Neel, including poet Adrienne Rich and art historian Mary Garrard, remember the artist interrogating them about their sexuality – perhaps a deliberate effort to engender the kind of discomfort that pervades so many of her portraits. Neel also was, in her own words, “not a good communist” any more than she was a model feminist. As a rule, Griffey writes in the catalog, she was “allergic to bureaucracy and dogma,” and to her credit that meant that, even very early on, she was able to separate her own moral, ethical and political positions from those of the movements she embraced. Although her relationship with what we now call the LGBTQ+ community was complex throughout her life, Baum says, she never participated in – and indeed rejected – the outright homophobia that pervaded left-wing political movements in the pre-World War II era.

She took that same contrariness into her opinions on art as well, unafraid to criticize, in the most unvarnished way, the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism and its dominance over the contemporary art world in the 1950s: “I am against abstract and non-objective art,” she said in the same 1950 interview that gives the present show its title, “because such art shows a hatred of human beings. It is an attempt to eliminate people from art.” Though she modified that stance later in life, acknowledging that all “great painting” has “good abstract qualities,” she remained resolutely a figure painter and portraitist, firmly rooted in the representational – and “paid a pretty heavy price for it,” Griffey says. She was as prolific as ever in the 1950s and early 1960s, but her work – which continued to highlight the working-class inhabitants of Harlem along with prominent feminists and women of color – was largely ignored by the predominantly white, male cohort of artists, critics and curators who saw anything other than pure abstraction as retardataire.

“The Spanish Family” by Alice Neel, 1943. Oil on canvas, 34 by 28 inches. ©The Estate of Alice Neel.

Griffey has observed that to follow the trajectory of Neel’s work is to witness a kind of visual history of the New York neighborhoods she lived in. However, after her 1962 move across town to the upper West side, neighborhood types appear less frequently in her work. She was also older by that time, and changing working habits may have affected her choice of subjects. Her process became more about calling on people from her network of friends, family members, colleagues and fellow artists to visit her in her home studio and perhaps sit for a portrait. This is how the double portrait of Hendricks and Buczak came to be; Hendricks remembered that they first visited her for a cup of coffee, and then, having clearly scoped them out as potential subjects, Neel invited them to return the next day for a sitting, wearing the same clothes. Color is like a third character in that dual portrait, just as it is in “Linda Nochlin and Daisy” of 1978; the sitters’ clothes, and how they cover and decorate their bodies, communicate much about them.

This is also when Neel began to paint celebrities, or at least the celebrity-adjacent, like Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd, opening her work up to new audiences and renewed acclaim. Her 1970 portrait of Andy Warhol – seated, eyes closed, his midsection scarred and bandaged after surviving a 1968 assassination attempt – is achingly vulnerable, not least because Neel has dialed down her usual bright palette to create a melancholic tone. “It just highlights without a doubt what an amazing colorist she was,” says Griffey. “The fact that she was makes it all the more powerful when she restrains her palette.” Also evident here is the sense that posing for Neel was invariably an uncomfortable experience, to a greater or a lesser extent. Like Warhol, so many of her sitters are seen from slightly above, suggesting that the artist sought out a dominant vantage point; her subjects also generally take on a somewhat hunched, rounded-shoulder pose, with guarded gestures like crossed arms and legs.

Whatever else this may suggest, it could reflect a rather understandable response to Neel’s habit of asking most of her sitters, at the outset, if they would take off their clothes. “Most said no,” Griffey deadpans. But some said yes, perhaps without fully appreciating that they would become the subjects of some of the nudest nudes in the Western canon – swollen bellies, drooping breasts, sex organs splayed out as if for display in a terrarium. Baum suggests that these works should perhaps be more correctly termed “nakeds”: “The ‘nude’ is a rarefied artistic genre that interests Neel not at all, or interests her only insofar as she can transgress and subvert it.” Griffey adds, “There’s a kind of metaphor around the nakedness because it is stripped bare… Neel could not abide by pretense or putting on airs.”

“Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian” by Alice Neel, 1978. Oil on canvas. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Purchase, by exchange, through an anonymous gift. ©The Estate of Alice Neel.

This is, of course, true of Neel’s portraits generally. There is a sense in which they are quite traditional – in genre, in composition, in materials – Neel herself described them as “old fashioned” easel paintings – but Griffey pushes against that perception. With her freehanded technique, he argues, she “allowed evidence of her brushwork and labor to remain,” a distinctly modern approach. The working-class subjects she often chose, while not unprecedented in portraiture, also firmly place her more in the modernist idiom than the circumscribed tradition of academic portraiture that preceded it. Further, the personal politics that are so evident in her work meaningfully connect her to issues of social justice that continue to be urgently felt today. Neel’s career “traces a trajectory of representation,” to paraphrase Griffey, speaking specifically about her LGBTQ+ subjects – but the phrase applies equally well to all the marginalized people she represented. They showed out for her, and she showed up for them. People came first.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue. For further information, 212-535-7710 or www.metmuseum.org.

"come" - Google News

March 30, 2021 at 11:56PM

https://ift.tt/3uaWqps

Alice Neel: People Come First - Antiques and the Arts Online - Antiques and the Arts Online

"come" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2S8UtrZ

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Alice Neel: People Come First - Antiques and the Arts Online - Antiques and the Arts Online"

Post a Comment